Articles

The inexorable rise of Third-Party Management (TPM) in financial institutions

Introduction As financial institutions increasingly evolve into a complex network of internal teams and external partners, the holistic management of third parties, encompassing value generation and risk management, is now…

Introduction

As financial institutions increasingly evolve into a complex network of internal teams and external partners, the holistic management of third parties, encompassing value generation and risk management, is now a strategic imperative.

While staff costs remain the single largest component of operating expenses for most financial institutions, the share of external spend, particularly in technology, outsourcing and specialist services, has grown significantly. This is reflective of the industry’s drive for efficiency, access to expert skills and rapid adaptation to digital and regulatory demands. This focus is now on optimising the mix of internal capabilities and external partnerships to best achieve strategic objectives. As a result, we are seeing the rise of virtual / networked companies, even in the highly regulated financial services industry.

Regulators have duly taken note, particularly of the associated risks, as they observe a growing shift of activities and infrastructure from regulated entities under their direct supervision, to un-regulated entities. In response we’ve seen a wave of new guidelines and requirements on Third-Party Risk Management (TPRM), including from the BIS, UK regulators and the ECB, all driven by operational resilience. Some regulators are even extending requirements directly to critical service provides, such as cloud services, as seen in frameworks like PS2/16.

In this landscape, where organisational boundaries blur and third parties effectively become extensions of a firm’s operations, the effective management and balancing of both value generation and the risks associated with third parties becomes critical. This has elevated Third-Party Management (TPM) from a back-office concern to a boardroom priority: a fusion of traditional Procurement and emerging TPRM practices.

How should organisations respond

TPM is a prerequisite for both resilience and success in today’s financial services and must now be developed as an organisational core capability. To do so effectively, organisations need to consider their approach across the following key dimensions:

1. Governance

Third parties are both a fundamental ‘factor of production’ and a critical stakeholder in the organisation – much like employees – and, in many respects, should be governed similarly. Indeed, the two factors are partially interchangeable depending on the buy vs in-house decisions taken by the business. As such, a TPM executive champion and management structure is essential if this is to become a core competence embedded throughout the organisation.

The governance of TPM must work within the established Board, Management and Three Lines of Defence model with each LoD and function playing its part in a highly coordinated manner.

2. Organisation and people

As with all activities, competences and disciplines – other than in very niche institutions – the perennial questions remain: to what extent should they be centralised vs decentralised? We can safely say that neither a totally centralised or totally decentralised model is feasible, but the exact balance will be driven by the institution’s size, scope, culture etc. It is essential that the respective roles, responsibilities and processes are clearly defined, socialised and embedded for sustainable success.

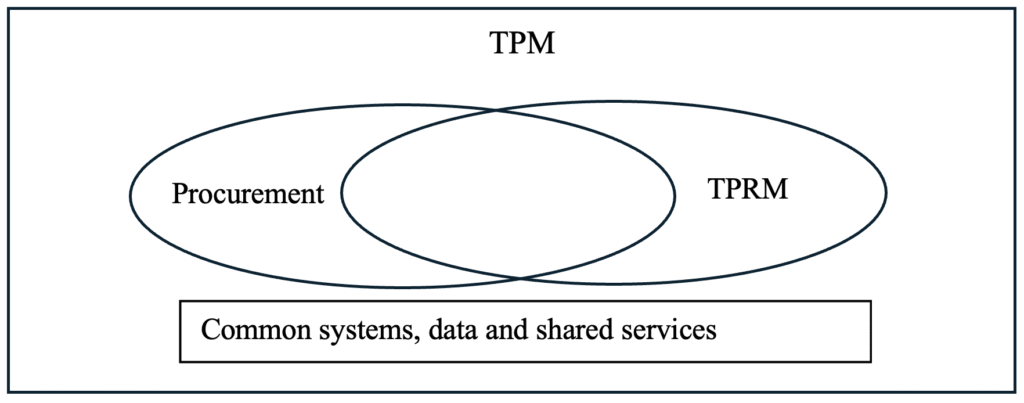

One key decision will be how best to integrate the traditional Procurement function and the newer TPRM discipline. The two are inextricably linked (effectively the risk and reward dimensions of a TP relationship) but also distinct. The relationship can be summarised in the following venn diagram:

Poor integration between Procurement and TPRM can lead to both inefficiency and risk. However, their differences need to be recognised, e.g. procurement is a commercial function with no direct oversight from the 2nd Line or regulatory reporting obligations, while TPRM has both requirements.

Adequate resourcing and skills are, of course, prerequisites of successful TPM. But great care is needed to avoid duplicating resources in the push to ensure compliance with the recent regulatory focus on TPRM. Many skills and resources will already exist in the organisation, e.g. under operational risk, cyber and information security, legal and compliance and should be fully aligned and leveraged.

3. Processes, roles and responsibilities

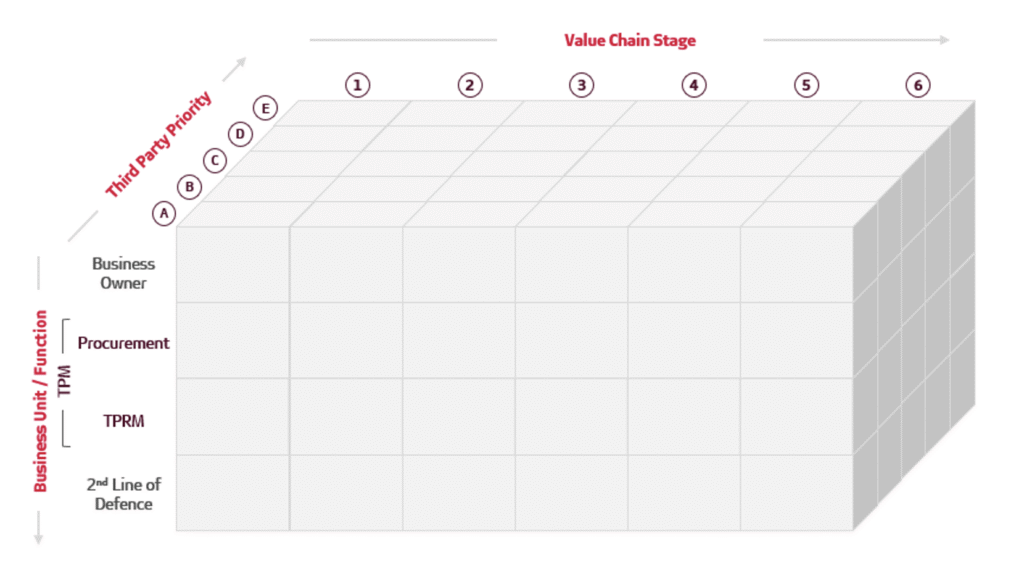

As TPM becomes an institution-wide discipline, ensuring that processes are standardised, clearly defined and socialised is essential. Processes including roles and responsibilities (RACI) need to be defined for all possible matrix combinations of each stage of the value chain (e.g. selection, DD and onboarding), business unit / function (1st line or support functions) and TP Rating (risk/business materiality), as illustrated by the following multi-dimensional TPM Matrix:

4. Technology and data

TPM lends itself to the extensive and innovative use of specialised software platforms for automation, workflow management and smart decision making. Serving as a strong use case for AI – particularly in identifying concentration and nth-order risks in the supply chain and smart contracts. However advanced tools will be rendered ineffective without good data. Corporate wide systems and processes to gather and standardise the necessary data will be essential, but this too can be enhanced by innovative technology, such as for market screening and early warning indicators.

An important footnote is that while we are here discussing the technology and tools for successful TPM, the effective management of technology and data providers in terms of value and risk is an increasing critical requirement for all organisations. For example, virtual networked models inherently increase the cyberattack surface. Each third-party with access to core systems or data may improve client service and STP but will also represents a potential entry point for malicious actors.

Conclusion

In a world increasingly defined by virtual, networked enterprises with complex, supply chains and multifarious risks, Third-Party Management must take centre stage as a core organisational capability.

This requires deep thinking about the business model, organisation, processes, people and technology tools – but also a fundamental cultural shift away from a reactive compliance-driven approach towards a proactive, risk-adjusted value approach that underpins operational resilience, financial security and long-term business success.